Antarctica 1958-1965

This is a presentation I gave at my youngest daughter’s primary school on 23 Sep 2025.

They were studying Shackleton’s Antarctic expeditions, and I thought I might be able to give some useful input given my dad spent a number of years in Antarctica. Although not facing quite the same level of challenges as Shackleton, the time he was there (1958 to 1965) was closer to Shackleton’s time than it is to now. He received a Polar Medal for his work as scientific leader, wrote a book on the subject, and used to give talks to schools.

One topic in class had been Shackleton’s purported “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful.” advert, and activities included discussing what sort of people would be applying and writing their own application letter. So the presentation tries to tie in with this, including:

- Specific challenges, both obvious, e.g. crevasses, and unexpected, e.g. trying to light a stove at -55C, and more general challenges, e.g. the isolation, darkness, etc.

- The report card from my dad’s employment file (minus his scores of course:-) which shows the characteristics they are looking for (i.e. one line about technical knowledge, one line about working hard, and almost everything else about getting on well with other people).

Also (spoiler alert), given the audience was 10-11 year olds, there are a few penguins:-)

My dad spent a number of years in Antarctica between 1958 and 1965, overwintering at least twice. I’m going to talk about some of the challenges he faced there, both obvious and unexpected.

It was an earlier era of Antarctic research and exploration, closer in time to Shackleton than to now.

Here’s his boat. It was metal rather than wood like Shackleton’s boat, but great care was still needed navigating ice.

It took 8 weeks at sea before first seeing ice, and then took several days to navigate through the different types of ice.

The ship stopped at a number of research stations, and it took days to offload with everyone (regardless of rank or job) working 16 hours a day to help unload.

The ships needed to provide everything everyone needed to live and work for a year, for example huts, generators, equipment and materials.

Here’s my dad in one of the supply stores.

You needed 2 years of food for all the people, just in case the supply ship couldn’t return the next year.

It is mostly canned food. You can even see cans of jam and cans of butter in the photo. And lots of coffee and sugar.

The bases were all different with different specialities.

This is Port Lockroy, which is on land, with specialities being research into the ionosphere, which is an electrically conductive layer in the atmosphere used (amongst other things) to allow world wide radio communications.

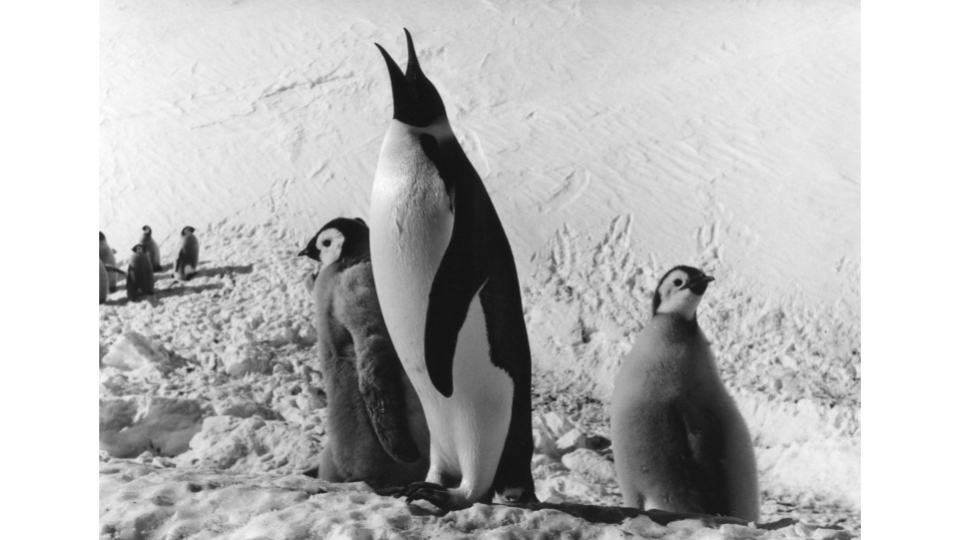

It is also close to a colony of Gentoo penguins.

Everyone likes penguins

Further south is Halley Bay.

This was built on an ice shelf over water. It was originally above ground level, but by the time this picture was taken, so much snow and ice had accumulated that it had become buried deep under the surface, accessed via a hatch and ladder down. (The new base at that location is on hydraulic legs and skis to prevent the same fate.)

It is an important station for research into the earth’s atmosphere, and research from here led to the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer in the early 1980s.

It is also close to the biggest colony of Emperor penguins.

More penguins!

One of the regular expeditions from Halley Bay was with the glacier expert going to the Dawson Lambton glacier to take measurements on how the ice was flowing. It was a camping trip. Some of you may have been camping. But camping in the Antarctic at minus 60 degrees centigrade has some additional challenges.

Firstly, the weight of rations and equipment for 2 people for 10 days was around 180kg, about the weight of 2 big adults. That had to be put on two sledges which were “manhauled” rather than pulled by dogs. Everything was doubled in case one sledge was lost.

One of the big fears was crevasses. These are incredibly deep cracks with sheer sides which open up as the ice moves. They are particularly dangerous in Antarctica because they are often hidden by “ice bridges” formed by the same snow and ice accumulation which completely buried the Halley Bay base. You can be on an ice bridge over a crevasse and not notice it, and it can sometimes take your weight, but it can also sometimes collapse. If you have a sledge led by dogs they would collapse a weak ice bridge first (they’re almost as heavy as a person and have all the weight concentrated on the paws) but because they are attached to the sledge you can generally pull them out as long as the sledge hasn’t gone down too. But with manhauling you need to make sure everyone is roped together, so if one person goes down the other can hopefully haul them out. There have been many cases where people have fallen down deep crevasses and their bodies never recovered.

You also need to be very careful how you move and dress when it is -60C. You need to keep moving to avoid freezing, but you can’t exert yourself too much because heavy breathing would risk damaging your lungs with freezing air and sweat would also risk freezing.

When setting up camp, you need to poke the ground with ski sticks to try to make sure you’re not pitching your tent on an ice bridge over a crevasse.

Everything you eat or drink has to be warmed, because otherwise your tongue would get frostbite. So you have a stove. But lighting a stove in those sorts of temperatures isn’t easy. You need to keep the matches close to your body so they don’t get too cold, and you can’t light the fuel at first because the fuel is too cold to so you have to use a few matches to warm up the fuel first.

Frostbite is another constant fear. You need to keep checking your colleague for signs of frostbite, and when you sleep at night you need to cover your face with a towel to avoid frostbite.

In addition to these specific challenges, you also have more general challenges when overwintering in Antarctica:

Isolation

- When the last supply ship leaves in summer, most people go with them, and you are alone with just the small group on the base for most of the next 6+ months. The photo shows the team at Scott Base (where my dad was scientific leader from 1962-1965) which is one of the larger bases.

- There is some radio contact with the outside world, but even that was lost for some days in the late 1950s due to solar flares.

- Letters can take 7-8 months to be delivered if they miss the last supply ship, so it could take a year to get a reply.

Darkness

- It takes 2 months to transition from the sun never setting to the last sunset.

- Then it is 4 months of darkness.

“Winter-over syndrome” (sometimes formerly known as “polar madness”)

- Some people can be prone to a variety of behavioural and medical disturbances, not just due to the cold, danger, and dark, but the social stresses of the isolation and close confinement and lack of privacy.

- There have been lots of studies of this, and some have been used to inform the space programme. With the dark, isolation and hostile environment, overwintering in Antarctica isn’t unlike being in space.

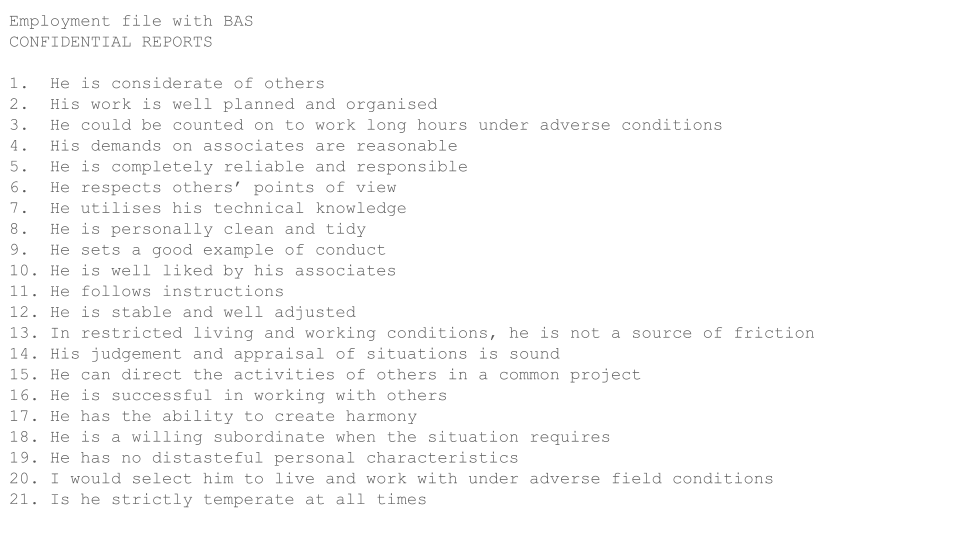

Being able to work well with anyone, even people you might not like, is a really useful skill to learn for any job, but it is much much more important for this sort of job, where you are essentially trapped with your colleagues for months at a time, in a very harsh environment where your very survival may depend on them.

At the end of every tour, it is standard practice for your employer to make a report card, kind-of like a school report.

Here’s the British Antarctic Survey report card from the era. People were graded 1-5 for each of the questions.

You can see a common theme in the questions: “considerate of others”, “reliable and responsible” “respects others” “stable and well adjusted” “not a source of friction” and “ability to create harmony”. Also “strictly temperate”.

For his work in Antarctica, my dad was awarded a Polar Medal in 1969, which he received from the queen in 1972. The medal shows the Shackleton’s RRS Discovery.

He also wrote a book about his time there. I’ll leave a copy with the school if anyone is interested.